Your Plate, Your Power: Navigating Type 1 Diabetes Food with Confidence

Let’s dive into Type1 Diabetes Food today. Receiving a Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) diagnosis can feel overwhelming, especially when it comes to food. For many, the joy of eating transforms into a landscape of anxiety, calculation, and even guilt. The thought of every bite impacting blood sugar levels can make food feel like an adversary, leading to stress and a sense of deprivation. It is a common experience to feel constantly judged or monitored regarding food choices, particularly for young adults, which can unfortunately contribute to negative patterns around eating.

However, this perspective can be profoundly shifted. Food is not an enemy; it is a powerful ally in managing blood glucose and enhancing overall well-being. A diet for Type 1 Diabetes is fundamentally a healthy eating plan, not a restrictive, specialized regimen. It is about making informed choices and understanding how to balance insulin with what is consumed, rather than focusing on deprivation. This understanding empowers individuals to regain control and foster a more flexible, enjoyable eating experience, paving the way for a full and vibrant life. This guide aims to provide practical, empathetic insights to help individuals confidently navigate their Type 1 Diabetes food choices, alleviate concerns, and transform their relationship with food.

Understanding the Basics: How Food Impacts Type 1 Diabetes

To effectively manage Type 1 Diabetes, it is essential to grasp how different components of food influence blood glucose levels. This foundational knowledge forms the basis for making informed dietary choices and precise insulin adjustments.

Macronutrient Roles

The primary components of food—carbohydrates, protein, and fat—each play a distinct role in affecting blood glucose.

Carbohydrates: These are the body’s main source of energy and the most direct determinant of blood glucose levels. During digestion, carbohydrates break down into glucose, which then enters the bloodstream. This rapid conversion means carbohydrates have the most significant and immediate impact on blood sugar. Understanding the quantity and type of carbohydrates consumed is therefore central to T1D management.

Protein and Fat: Protein and fat do not cause an immediate, rapid rise in blood glucose in the same way carbohydrates do. However, they significantly influence the speed at which carbohydrates are absorbed and can lead to a delayed and prolonged elevation in blood sugar, especially when consumed in larger quantities.

Proteins are converted into glucose through a process called gluconeogenesis.

This takes place when amino acids are converted into glucose after the meal.

✅ Eat plant based proteins.

Fat, on the other hand, primarily delays stomach emptying. This mean food stays in the stomach longer, slowing down the absorption of carbohydrates.

In turn this causes a later, extended blood glucose peak, sometimes occurring 3 to 8 hours after the meal.

✅AVOID ANIMAL AND PROCESSED FATS LIKE THE COVID

✅ EAT PLANT FATS IN MODERATION

This complex interaction, where fat and protein act as “late-comers” to the glycemic response, is a critical aspect.

It is ofen overlooked in a purely carbohydrate-focused approach to dietary intake in Type 1 diabetes.

Recognizing this delayed effect is vital for preventing unexpected post-meal highs and achieving more stable blood glucose levels.

–

Fiber: Dietary fiber, found in plant foods, is a type of carbohydrate that the body cannot digest or absorb. Consequently, it does not directly raise blood glucose levels. Instead, fiber plays a beneficial role by moderating how the body digests food, which helps control blood sugar levels. It also contributes to a feeling of fullness, aiding in weight management and promoting overall digestive health.

The Importance of Balanced Meals

Combining these macronutrients strategically is key to achieving better blood sugar control. Eating carbohydrates alongside foods rich in protein, fat, or fiber slows down how quickly glucose is absorbed into the bloodstream, leading to a more gradual and predictable rise in blood sugar. For example, consuming whole fruit (rich in fiber) will raise blood sugar slower than drinking fruit juice (which lacks fiber). This balanced approach helps prevent sharp spikes and subsequent crashes.

Embracing a “No Bad Food” Philosophy

A common pitfall in diabetes management is labeling certain foods as “good” or “bad.” This categorization can foster feelings of guilt and shame around eating, increasing the risk of developing disordered eating patterns. It is crucial to understand that no food is inherently “bad” or “forbidden” when living with Type 1 Diabetes. The emphasis should be on making informed choices, practicing portion control, and balancing insulin doses to enjoy a wide variety of foods. This approach helps cultivate a healthier, more sustainable relationship with eating, moving away from rigid restrictions towards flexible, empowered choices.

The Cornerstone of T1D Food Management: Carbohydrate Counting

Carbohydrate counting stands as a fundamental and empowering strategy for managing Type 1 Diabetes. It is the process of tracking the total grams of carbohydrates in a meal or snack and then matching that amount to the appropriate insulin dosage.

This practice is crucial because it offers individuals with Type 1 Diabetes unparalleled freedom and spontaneity in their food choices and meal times. This is especially important when combined with flexible insulin regimens like basal-bolus therapy or the use of insulin pumps. Instead of adhering to a rigid, regimented diet, individuals can adjust their insulin to cover what they choose to eat, leading to better blood glucose control and a significantly improved quality of life. This transformation moves individuals from feeling constrained by their condition to actively controlling it, allowing them to enjoy social events and diverse cuisines without constant worry.

Practical Tips for Carbohydrate Counting

Mastering carbohydrate counting involves a combination of label reading, estimation skills, and leveraging technology.

Reading Nutrition Labels: For packaged foods, the “Nutrition Facts Label” is an invaluable tool. Focus on three key elements: the serving size, the number of servings per container, and the total carbohydrates per serving. It is important to note that dietary fiber, though listed under total carbohydrates, is not digested by the body and therefore does not raise blood glucose. For a more accurate insulin dose calculation, the grams of fiber can often be subtracted from the total carbohydrate count.

Counting Without Labels: Estimating carbohydrate content for unpackaged or homemade foods requires a different approach. Utilizing food lists that group similar foods by their carbohydrate content can be highly effective. For instance, many food items are categorized so that one “carb serving” equates to approximately 15 grams of carbohydrate.

Developing an intuitive understanding of portion sizes is also immensely helpful. This can be achieved by “training your eye” at home. Regularly measuring foods with cups or scales helps build a visual memory of typical portion sizes, which then allows for more confident and accurate estimation in situations where labels or measuring tools are unavailable, such as dining out. This skill fosters greater independence and reduces reliance on external tools, making diabetes management more seamless in daily life.

Leveraging Technology: Modern technology offers significant support for carbohydrate counting. Various carb calculator apps and websites can simplify the process, especially when dining out or preparing complex meals with multiple ingredients. These tools can provide quick access to nutritional information for a vast array of foods.

Practice Makes Perfect: While carbohydrate counting may seem daunting at first, consistent practice and experience make it “second nature”. Like any new skill, it improves over time, leading to greater confidence and precision in managing blood glucose levels.

Insulin-to-Carbohydrate Ratio (ICR)

A personalized Insulin-to-Carbohydrate Ratio (ICR) is a fundamental component of flexible insulin therapy. This ratio indicates how many grams of carbohydrate are covered by one unit of rapid-acting insulin. For example, if an individual’s ICR is 1:10, it means they take 1 unit of insulin for every 10 grams of carbohydrates consumed. To calculate the required insulin dose, one simply divides the total grams of carbohydrates in a meal by their personalized ICR. This precise calculation allows for tailored insulin delivery, accommodating varying meal sizes and compositions.

Table 1: Quick Carb Counting Guide (Approx. 15g Carb Servings)

| Food Group | Food Item | Approximate Serving Size (for 15g carbs) |

| Starches | Cooked Rice/Pasta | 1/3 cup |

| Bread | 1 slice (1 oz) | |

| Cooked Oatmeal | 1/2 cup | |

| Saltine Crackers | 6 crackers | |

| Small Potato | 1 small (100g) | |

| Corn or Green Peas | 1/2 cup | |

| Fruits | Small Apple | 1 small (4 oz) |

| Grapes | 17 small (3 oz) | |

| Fruit Juice (unsweetened) | 1/2 cup | |

| Medium Banana | 1/2 medium | |

| Blueberries | 3/4 cup | |

| Milk & Dairy | Low-fat or Non-fat Milk | 1 cup |

| Plain Yogurt | 1 cup |

Note: Serving sizes are approximate and can vary by brand and preparation. Always verify with nutrition labels or a registered dietitian.

Building Your Plate: The Diabetes Plate Method & Beyond

Meal planning for Type 1 Diabetes does not have to be complicated or rigid. The Diabetes Plate Method offers a simple, visual, and highly effective approach to creating balanced meals without the need for meticulous counting at every single meal. This method is particularly valuable for reducing the cognitive load associated with daily meal planning, making healthy eating more accessible and less intimidating. It simplifies the decision-making process, contributing to greater consistency and preventing burnout in diabetes management.

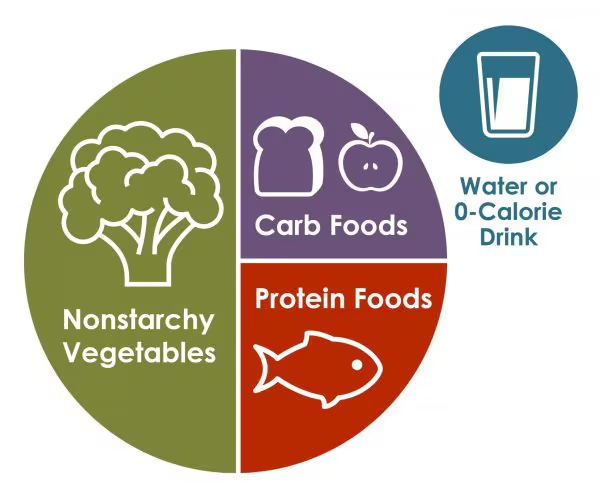

The Diabetes Plate Method

The core of this method involves a standard 9-inch dinner plate, visually divided into three sections:

Half the Plate: Non-Starchy Vegetables: Fill half of your plate with a variety of non-starchy vegetables. These are low in carbohydrates and rich in vitamins, minerals, and fiber, making them excellent choices to consume in abundance.

Examples include spinach, kale, broccoli, carrots, bell peppers, green beans, cucumbers, and zucchini.

One Quarter of the Plate: Lean Protein: Dedicate one quarter of your plate to a lean protein source. Protein helps with satiety and has a minimal immediate impact on blood glucose, though it can influence the speed of digestion.

Good choices include skinless chicken, fish (especially omega-3 rich varieties like salmon, mackerel, tuna, sardines), legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas), tofu, eggs, and lean cuts of pork or beef.

One Quarter of the Plate: Carbohydrate-Rich Foods: The remaining quarter of your plate should be for carbohydrate-rich foods. Prioritize complex carbohydrates that are high in fiber and nutrients.

This includes whole grains like brown rice, quinoa, oats, and whole wheat bread or pasta; whole fruits (eating the whole fruit rather than just juice maximizes fiber benefits); and low-fat dairy products such as milk and plain yogurt.

Using a standard 9-inch plate naturally guides portion sizing, which is crucial for managing blood sugar effectively and preventing overeating.

Recommended Food Groups and Foods Include

While the Plate Method provides a visual framework, understanding specific food choices within each category is important.

Non-Starchy Vegetables: These can be enjoyed freely due to their low carbohydrate content and high nutritional value. Examples include artichokes, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, celery, dark leafy greens, eggplant, mushrooms, onions, radishes, and tomatoes.

Healthy Carbohydrates: Focus on less processed options with minimal added sugars and higher fiber content. This includes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and low-fat dairy products. The consistent emphasis across various health organizations on whole foods and minimally processed options is a core principle for optimal health in Type 1 Diabetes.

These foods, rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals, lead to slower and more stable glucose absorption, contributing to better blood glucose control and reducing the risk of long-term complications like heart disease.

Lean Proteins: Opt for protein sources that are lower in saturated fat. Beyond the examples mentioned above, nuts and tofu are also excellent choices.

“Good” Fats: Include sources of healthy fats like avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil. These monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats are beneficial for heart health by lowering LDL cholesterol. However, it is important to remember that all fats are calorie-dense, so portion control remains essential.

Recommended Food Groups and Foods To Limit

Foods to Limit/Choose Less Often: Certain food categories should be limited due to their higher impact on blood sugar or overall health. These include foods high in added sugars (e.g., sodas, sweetened fruit juices, some yogurts), refined grains (e.g., white bread, white flour, white rice), saturated fats (e.g., high-fat dairy, processed meats like bacon and hot dogs, butter, coconut oil), trans fats (e.g., in processed snacks, baked goods), and excessive sodium.

It is vital to reiterate the “no bad food” philosophy here; the goal is to make informed choices about how often and in what quantity these foods are consumed, rather than outright avoidance, to prevent guilt and support a healthy relationship with food.

Exploring Diverse Healthy Eating Patterns

While the Plate Method is an excellent starting point, individuals can explore various healthy eating patterns that align with their preferences and health goals. Examples include:

Mediterranean Diet: Rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and heart-healthy fats, with moderate amounts of fish and dairy, and limited red meat.

Plant-Based Diets: Focusing on increased vegetables, grains, legumes, and fruits, these diets have shown promise in improving insulin sensitivity, reducing insulin requirements, and improving cardiovascular and renal health markers in individuals with Type 1 Diabetes.

Low-Carbohydrate Approaches: Some individuals may explore low-carb diets to help reduce A1C, achieve weight loss, or improve blood pressure and cholesterol levels. These diets typically emphasize non-starchy vegetables, healthy fats, and protein, with limited quality carbohydrates.

Any significant dietary changes, especially for Type 1 Diabetes, should always be made in consultation with a registered dietitian or healthcare provider to ensure they are safe, effective, and tailored to individual needs and insulin regimens.

Beyond Carbs: The Role of Protein, Fat, and Fiber

While carbohydrates are the primary focus of insulin dosing, understanding the nuanced effects of protein, fat, and fiber is crucial for achieving optimal blood glucose control in Type 1 Diabetes. These macronutrients, often overlooked in their complexity, can significantly influence the timing and magnitude of post-meal blood glucose responses.

Protein’s Impact

Protein generally has a minimal direct effect on immediate blood glucose levels when adequate insulin is present. However, its influence is more subtle and delayed.

Protein can lead to a delayed rise in blood glucose, particularly when consumed in combination with carbohydrates. This occurs partly due to gluconeogenesis, the process by which the liver converts amino acids from protein into glucose.

Beyond its glycemic impact, protein is vital for promoting satiety, helping individuals feel full and satisfied, which can aid in overall meal management and prevent overeating. It also helps stabilize blood sugar levels by slowing down the overall digestion of a meal.

Plant Protein and Diabetes:

Heart Health: Plant-based diets, generally rich in plant proteins, are associated with lower blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and a reduced risk of heart disease, which is a common complication of diabetes.

Improved Glycemic Control: Plant-based proteins generally have a minimal impact on blood glucose levels. Many plant protein sources (like legumes, nuts, and seeds) are rich in fiber, which helps slow down sugar absorption, leading to more stable blood sugar levels and reduced post-meal spikes.

Reduced Insulin Resistance: The fiber and lower saturated fat content in plant proteins can help reduce the body’s resistance to insulin, a key factor in type 2 diabetes development and management.

Weight Management: Plant-based proteins are often lower in calories and saturated fat, and their high fiber content can promote satiety, aiding in weight loss – a crucial aspect of diabetes prevention and treatment.

Reduced Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Numerous studies suggest that higher consumption of plant protein is associated with a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This benefit is often attributed to the overall nutrient profile of plant foods, including fiber, antioxidants, and beneficial fats.

Fat’s Impact

Fat has little, if any, immediate effect on blood glucose levels. However, its significant impact on blood sugar control lies in its ability to

delay gastric emptying. This means that when carbohydrates are consumed with a significant amount of fat, the digestion and absorption of those carbohydrates are slowed down considerably. This often results in a

delayed and prolonged peak in blood glucose, which can occur anywhere from 3 to 8 hours after the meal. This “late-comer” effect of fat and protein is a common source of frustration for individuals who only account for immediate carbohydrate impact, leading to unexpected and prolonged high blood glucose levels hours after eating.

Furthermore, a high intake of certain fats, particularly saturated fat, can contribute to insulin resistance, making it harder for insulin to work effectively in the body. While healthy fats (like omega-3s, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats found in fish, avocados, nuts, and olive oil) are vital for heart health, they are calorie-dense and should be consumed in moderation.

The Power of Fiber

Fiber, a non-digestible carbohydrate found in plant foods, plays a vital role in blood glucose management. It slows down digestion and the absorption of glucose, contributing to more stable blood sugar levels. Beyond glycemic control, fiber also helps improve cholesterol levels and aids in weight management by promoting a feeling of fullness without adding significant calories. Including plenty of fiber-rich foods like vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, and seeds is a cornerstone of a healthy Type 1 Diabetes eating plan.

Adjusting Insulin for High-Fat/High-Protein Meals (Advanced Consideration)

Meals that are high in both fat and protein (such as pizza, burgers, or some creamy pasta dishes) are notorious for causing unexpected and prolonged high blood glucose levels hours after consumption. This is precisely due to the delayed absorption discussed above. For individuals using insulin pumps, the concept of “extended boluses,” “square wave boluses,” or “dual wave boluses” is a valuable strategy to address this challenge. These advanced bolus types allow a portion of the insulin to be delivered immediately, while the remainder is delivered gradually over several hours, better matching the delayed glucose absorption from fat and protein.

Some advanced methods, like Fat-Protein Units (FPUs), estimate additional insulin requirements based on the caloric content of fat and protein. One FPU (approximately 100 kilocalories from fat or protein) is thought to roughly approximate the insulin requirement for 10 grams of carbohydrates.

General guidelines for adjusting insulin for these meals, often requiring individualized trial and error, might involve increasing the calculated meal bolus by 20-35%. For pump users, a suggested starting split could be delivering 50-60% of this new dose as a normal pre-meal bolus, with the remaining 40-50% delivered as an extended wave over 2-3 hours. For individuals using multiple daily injections (MDI), delivering extended boluses is more challenging. In these cases, it is recommended to closely monitor blood glucose levels at 1.5, 3, and 6 hours post-meal to understand the individual’s unique response to such meals and discuss potential adjustments with their diabetes care team.

Table 2: Insulin Adjustment for High-Fat/High-Protein Meals (Only under the guidance of a doctor)

| Meal Type Examples | Characteristics (Approximate) | Suggested Insulin Adjustment (Pump Users) | Suggested Bolus Delivery (Pump Users) | Monitoring Tip (MDI Users) | Important Note |

| Pizza, Burgers, Creamy Pasta, Fried Foods, Chinese Takeout | >40g Fat AND/OR >25g Protein with carbohydrates | Add 20-35% to carbohydrate bolus | 50-60% immediately, 40-50% extended over 2-3 hours | Check blood glucose at 1.5, 3, and 6 hours post-meal | These are general guidelines. Individual responses vary significantly. Always consult your diabetes care team for personalized advice and adjustments. |

Addressing Concerns & Fostering a Healthy Relationship with Food

The journey with Type 1 Diabetes often presents significant emotional and psychological hurdles related to food. Many individuals experience intense fears and challenges that can undermine their well-being and glycemic control.

Common Concerns & Challenges

Fear of Hypoglycemia (Hypos): The intense worry about low blood sugar can lead to behaviors such as overeating to prevent drops or avoiding certain foods perceived as risky. This can inadvertently contribute to weight gain or disordered eating patterns.

Fear of Hyperglycemia (Spikes): While glucose monitoring is a vital management tool, constant feedback on blood sugar spikes can paradoxically fuel obsessive thoughts about food’s “negative” effects. This can lead to highly restrictive eating patterns, feelings of guilt after eating, and even the avoidance of beloved foods. It’s a complex dynamic where a tool designed for control can, if not managed mindfully, contribute to anxiety and an unhealthy relationship with food. It is important to remember that blood glucose curves are not always flat, even in individuals without diabetes.

Judgment & Body Image Pressure: Particularly for adolescents and young adults, the constant scrutiny of food choices, combined with societal pressures around body image, can significantly increase the risk of developing disordered eating patterns, a risk that is notably higher in individuals with Type 1 Diabetes.

Loss of Enjoyment: For many, food transforms from a source of pleasure and social connection into a chore, a series of calculations, or a constant source of anxiety. This erosion of enjoyment can impact overall quality of life.

Mindful Eating Strategies

Mindful eating is a powerful and compassionate tool that can help individuals reconnect with their body’s hunger and satiety signals, reduce emotional eating, and bring joy back to mealtimes. It complements carbohydrate counting by fostering a healthier emotional response to food.

Practical Steps for Mindful Eating:

- Create a Dedicated Space: Make a conscious effort to sit down at a table for meals, avoiding the habit of standing or grazing.

- Eliminate Distractions: Put away phones, turn off the television, and minimize other distractions. The goal is to focus entirely on the meal in front of you.

- Engage All Senses: Before and during eating, take time to notice the visual appearance, aroma, textures, and tastes of your food. A simple exercise, like slowly savoring a single raisin, can illustrate the richness of this experience.

- Eat Slowly and Chew Thoroughly: This allows your body sufficient time to register fullness signals, preventing overeating.

- Check In with Yourself: Regularly ask yourself: “Why am I eating? Am I truly physically hungry, or am I eating due to boredom, stress, anger, sadness, or loneliness?” Pay attention to how your body feels before, during, and after you eat, noting any feelings of hypo- or hyperglycemia.

- Pause Before Second Servings: Give yourself at least 15 minutes after finishing your first portion to assess if you are genuinely still hungry before reaching for more food.

- Complement, Not Replace: Mindful eating is a valuable complement to carbohydrate counting and reading food labels; it is not a replacement for these essential management tools.

Overcoming Food Anxiety & Guilt

- No “Forbidden” Foods: Reiterate the crucial message that no food is inherently “forbidden” or “glucose-damaging.” The focus should be on balance, portion control, and appropriate insulin dosing, rather than strict avoidance. Labeling foods as “bad” is detrimental to developing a healthy relationship with food. The ability to make informed, adaptable choices, rather than adhering to rigid rules, transforms the experience of living with Type 1 Diabetes from being controlled by the disease to actively controlling it within one’s life. This redefinition of “control” from restriction to empowerment is paramount for long-term psychological well-being and preventing burnout.

- Gradual Introduction of Feared Foods: For foods that cause anxiety or have been avoided, a compassionate approach involves introducing them in safe, controlled environments (e.g., at home when blood glucose is stable) and in small quantities. This helps individuals learn how to manage them, gradually building confidence and reducing fear over time.

- Develop Alternative Coping Strategies: Encourage individuals to identify and develop non-food-related ways to cope with difficult emotions or stress. Examples include practicing diaphragmatic breathing, reframing negative thoughts into more constructive ones, going for a walk, listening to music, or engaging in other self-care hobbies.

- Seek Professional Support: If food-related distress is intense, prolonged, or significantly impacts glycemic control and emotional well-being, seeking joint intervention from a psychologist and a registered nutritionist is essential. A comprehensive psychonutritional approach can provide tailored strategies and support to navigate these complex challenges.

Real-Life Scenarios: Navigating Food in Different Situations

Managing Type 1 Diabetes involves navigating various real-life food situations, from dining out to sick days and exercise. Having a plan for these scenarios can significantly reduce stress and improve blood glucose control.

Eating Out with Type 1 Diabetes

Dining out can be a source of anxiety, but with preparation and smart strategies, it can be an enjoyable experience.

- Preparation is Key: Empower yourself by proactively reviewing restaurant menus and nutrition facts online before you go. This allows for informed choices and pre-planning of insulin doses.

- Don’t Be Afraid to Ask: Inquire about food preparation methods, ingredients, and request sauces, gravies, or dressings on the side. This provides greater control over carbohydrate and fat intake.

- Smart Portion Control Strategies: Implement practical tips like sharing a meal with a dining companion, using a smaller plate at buffets, or asking for half of your meal to be boxed up for later before you even begin eating.

- Safe Bets: When the menu is overwhelming, reliable, lower-carbohydrate options like lean protein (e.g., grilled fish or chicken) and plenty of non-starchy vegetables are excellent go-to choices.

- Leverage Carbohydrate Counting Skills: Continue to utilize your carbohydrate counting knowledge, whether through estimation or a carb calculator app, even when eating out.

- Make Special Requests: Most restaurants are accommodating to dietary needs. Do not hesitate to speak up for your health.

Sick Days & Type 1 Diabetes Food Management

Illness can significantly impact blood glucose levels, making sick day management a critical aspect of T1D care.

- Crucial: Do NOT Stop Insulin: This is a vital message. Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes must continue taking their usual insulin doses, even if they are unable to eat. Illness and the body’s stress response can cause blood sugar levels to rise significantly, even without food intake.

- Monitor Frequently: Check blood sugar levels every 2 to 4 hours. If blood glucose levels are elevated (e.g., 240 mg/dL or greater, or >14 mmol/L), test for ketones in blood or urine, as these can indicate a serious condition like diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

- Hydration is Paramount: Staying well-hydrated is critical to prevent dehydration and help lower blood glucose. Drink plenty of sugar-free fluids (water, diet soda, clear broth, unsweetened tea) every hour.

- Easy-to-Digest Carbohydrates for Energy: If regular meals cannot be tolerated due to nausea or vomiting, consume small, frequent amounts of easy-to-digest carbohydrates to prevent hypoglycemia and provide essential energy. Aim for about 15 grams of carbohydrates every hour, or approximately 50 grams every 4 hours. Examples include fruit juice, regular soda, crackers, unsweetened applesauce, popsicles, instant cooked cereals, and regular gelatin.

- When to Call Your Doctor: Seek immediate medical attention if experiencing persistently high blood glucose readings (e.g., >300 mg/dL on two consecutive measurements that are not responsive to increasing insulin and fluids), moderate to large urine ketones, vomiting more than once, severe diarrhea lasting more than six hours, inability to keep liquids down for more than 4 hours, or significant weight loss during the illness.

Exercise, Nutrition & Type 1 Diabetes

Physical activity is an important part of a healthy lifestyle for individuals with Type 1 Diabetes, but it requires careful planning to maintain blood glucose stability.

- Balance is Key: Successful exercise with Type 1 Diabetes necessitates a careful balance between insulin doses, food intake, and the intensity and duration of physical activity. The body’s blood glucose response to exercise is highly individualized and depends on pre-exercise blood glucose levels, activity intensity, duration, and recent insulin adjustments.

- Pre-Exercise Snacking Guidelines:

- Check Blood Glucose (BG): Always check blood glucose 15-30 minutes before starting exercise.

- If BG is Low (<100 mg/dL): Consume 15-30 grams of carbohydrates (without covering with insulin) to raise blood sugar and reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, especially if exercising for more than 30 minutes.

- If BG is in Target (80-180 mg/dL): 15-30 grams of carbohydrates may still be needed, particularly for longer exercise sessions.

- If BG is High (>250 mg/dL): Check for ketones in blood or urine. If ketones are present, avoid vigorous activity until they clear, as exercise can worsen the situation and lead to DKA.

- During Exercise: Always carry fast-acting carbohydrates (e.g., glucose tabs, juice, energy gels) to treat unexpected lows. For prolonged activities, it is often recommended to consume an additional 15 grams of carbohydrates every 30-60 minutes. Staying well-hydrated by drinking plenty of water throughout the activity is also essential.

Conclusions & Recommendations

Navigating food with Type 1 Diabetes can initially feel like a daunting challenge, but it is a journey towards empowerment and a richer, more flexible life. The core principle lies in understanding how different macronutrients impact blood glucose and mastering carbohydrate counting, which, when paired with modern flexible insulin regimens, transforms a perceived limitation into a gateway for dietary freedom.

The Diabetes Plate Method offers a simple, visual guide for balanced eating, reducing the mental burden of constant calculation. Beyond immediate carbohydrate impact, recognizing the “late-comer” effect of protein and fat on blood glucose is crucial for preventing unexpected spikes and achieving more stable control, often requiring advanced insulin strategies like extended boluses.

Crucially, fostering a healthy relationship with food goes beyond numbers. Addressing fears of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, understanding the potential for food anxiety stemming from constant monitoring, and embracing mindful eating practices are vital. This shift redefines “control” not as rigid restriction, but as the ability to make informed, adaptable choices that integrate seamlessly into one’s lifestyle, allowing for enjoyment without guilt.

For real-life scenarios like dining out, sick days, and exercise, preparation, vigilant monitoring, and targeted nutritional adjustments are key. These practical strategies, combined with the foundational knowledge of food’s impact and a positive mindset, enable individuals with Type 1 Diabetes to confidently manage their health, reduce stress, and truly savor their meals and their lives. Always remember to consult with a diabetes care team, including a registered dietitian, for personalized advice and support.

FAQ

Q: Is there a specific “diabetes diet” for Type 1 Diabetes? A: No, there isn’t a single, rigid “diabetes diet” that applies to everyone. For people with Type 1 Diabetes, the recommended approach is a healthy, balanced eating plan that is naturally rich in nutrients, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, similar to general healthy eating guidelines. The key is to learn how different foods affect your blood glucose and to balance your insulin doses accordingly.

Q: Can people with Type 1 Diabetes still eat sugar or sweets? Eat low – glycemic foods only. Sugary foods can even be helpful for treating low blood sugar (hypoglycemia).

Q: How do protein and fat affect blood sugar levels, and how does this impact insulin timing? A: While carbohydrates have the most immediate impact, protein and fat can cause a delayed and prolonged rise in blood glucose, often hours after a meal. This is because fat slows down digestion, and protein can be converted to glucose over time. For individuals using insulin pumps, this often means utilizing “extended” or “dual wave” boluses to deliver insulin gradually over several hours to match this delayed absorption. For those on injections, monitoring blood glucose several hours after high-fat/high-protein meals is important to understand individual responses.

Q: Are artificial sweeteners recommended for people with Type 1 Diabetes? A: Artificial sweeteners do not typically raise blood glucose levels and contain no calories. While the pure sweetener itself may have a GI of 0, many commercial sweetener products contain bulking agents or other ingredients (like dextrose or maltodextrin) that can raise the glycemic index. Therefore, avoid them.

Always check the ingredient list if you’re concerned about blood sugar impact. the overall emphasis should be on consuming unrefined, whole foods, with an emphasis on vegetables. Naturally sweet foods like fruits and vegetables can taste sweeter when less added sugar is consumed.

Q: How can I estimate carbohydrate portions when there are no food labels? A: You can use food lists that group similar foods, where one “carb serving” is typically about 15 grams of carbohydrates. Additionally, practicing portion estimation at home using measuring cups or scales can help you “train your eye” to accurately estimate amounts when dining out or preparing homemade meals without labels. Mobile apps can also be a helpful tool.

References

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Carbohydrate Counting for Success. Diabetes Food Hub. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/food-nutrition/meal-planning

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Eating for Diabetes Management. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/food-nutrition/eating-for-diabetes-management

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Exercise & Type 1. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/health-wellness/fitness/exercise-and-type-1

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Living with Type 1: Type 1 Self-Care Manual. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/type-1/type-1-self-care-manual

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Sick Days. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/getting-sick-with-diabetes/sick-days

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Stay on Track During the Holidays. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/health-wellness/weight-management/stay-pn-track-during-holidays

British Dietetic Association. (n.d.). Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/diabetes-type-1.html

Breakthrough T1D. (n.d.). Nutrition and T1D. Retrieved from https://breakthrought1d.ca/life-with-t1d/nutrition/

Breakthrough T1D. (n.d.). Nutrition for Kids and Teens with T1D. Retrieved from https://www.breakthrought1d.org/illinois/wp-content/uploads/sites/71/2016/03/Nutrition-for-kids-teens-with-t1d-jdrf-030516-022216-final.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Carb Counting to Manage Blood Sugar. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/healthy-eating/carb-counting-manage-blood-sugar.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Common Foods That Contain Carbs and Serving Sizes (Starches). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/healthy-eating/carbohydrate-lists-starchy-foods.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Diabetes Meal Planning. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/healthy-eating/diabetes-meal-planning.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Managing Sick Days. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/living-with/managing-sick-days.html

Children’s Hospital at Westmead. (n.d.). Reluctant Eating and Type 1 Diabetes in Children: Management of. Retrieved from https://www.cuh.nhs.uk/patient-information/reluctant-eating-and-type-1-diabetes-in-children-management-of/

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (n.d.). Insulin-to-Carb Ratios: Calculate Meal Insulin Doses for Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://uihc.org/childrens/health-topics/insulin-carb-ratios-calculate-meal-insulin-doses-type-1-diabetes

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Type 1 Diabetes Diet. Retrieved from https://health.clevelandclinic.org/type-1-diabetes-diet

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21500-type-1-diabetes

DAFNE. (n.d.). What is DAFNE?. Retrieved from https://dafne.nhs.uk/

Diabetes Action. (n.d.). Questions Food and Diet. Retrieved from https://diabetesaction.org/questions-food-and-diet

Diabetes Canada. (n.d.). Glycemic Index Food Guide. Retrieved from https://guidelines.diabetes.ca/GuideLines/media/Docs/Patient%20Resources/glycemic-index-food-guide.pdf

Diabetes Teaching Center at UCSF. (n.d.). Counting Carbohydrates Without Food Labels. Retrieved from https://diabetesteachingcenter.ucsf.edu/living-diabetes/diet-nutrition/understanding-carbohydrates/counting-carbohydrates-without-food-labels

Diabetes Teaching Center at UCSF. (n.d.). Learning to Read Labels. Retrieved from https://diabetesteachingcenter.ucsf.edu/living-diabetes/diet-nutrition/understanding-carbohydrates/learning-read-labels

Healthline. (n.d.). Type 1 Diabetes Diet. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/type-1-diabetes-diet

Healthline. (n.d.). Low Glycemic Diet. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/low-glycemic-diet

Hopkins Diabetes Info. (n.d.). Ask the Dietitian. Retrieved from https://hopkinsdiabetesinfo.org/ask-the-dietician/

Hopkins Diabetes Info. (n.d.). Insulin Treatment in Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://hopkinsdiabetesinfo.org/insulin-treatment-in-type-1-diabetes/

International Diabetes Federation. (n.d.). Welcome to IDF. Retrieved from https://idf.org/

Know Diabetes. (n.d.). Insulin Dose Adjustment. Retrieved from https://www.knowdiabetes.org.uk/know-more/type-1-diabetes/insulin/insulin-dose-adjustment/

Mass General Brigham. (n.d.). Exercising with Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.massgeneral.org/children/diabetes/exercising-with-type-1-diabetes

Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Diabetes Diet: Eating Healthy with Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/in-depth/diabetes-diet/art-20044295

MedlinePlus. (n.d.). Glycemic Index and Diabetes. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000941.htm

My Type 1 Diabetes. (n.d.). The Glycaemic Index. Retrieved from https://www.mytype1diabetes.nhs.uk/resources/internal/the-glycaemic-index/

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (n.d.). Healthy Living with Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/healthy-living-with-diabetes

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (n.d.). Sick Day Management for Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.nebraskamed.com/sites/default/files/documents/Diabetes/10_9212%20Sick%20Day_Type%201.pdf

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (n.d.). Sick Day Management for Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.uhn.ca/PatientsFamilies/Health_Information/Health_Topics/Documents/Sick_day_management_Type_1_diabetes_dose_scale.pdf

NDSS. (n.d.). Carbohydrate Counting. Retrieved from https://www.ndss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/fact-sheet-carbohydrate-counting.pdf

Northwestern Medicine. (n.d.). Diabetes Meal Planning. Retrieved from https://www.nm.org/-/media/northwestern/resources/care-areas/diabetes/northwestern-medicine-diabetes-meal-planning-en.pdf

Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. (2023). Effect of a Dietary Intervention on Insulin Sensitivity and Insulin Requirements in Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clinical Diabetes, 42(3), 419-427. Retrieved from https://diabetesjournals.org/clinical/article/42/3/419/154329/Effect-of-a-Dietary-Intervention-on-Insulin

Revista Diabetes. (2024). Is a good relationship with food possible in type 1 diabetes?. Diabetes Psychology, 87, 48-52. Retrieved from https://www.revistadiabetes.org/wp-content/uploads/Is-a-good-relationship-with-food-possible-in-type-1-diabetes.pdf

Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. (n.d.). Adjusting Insulin. Retrieved from https://www.rch.org.au/diabetes/type-1-diabetes-toolkit/Adjusting_insulin/

Siddiqui, S. (2020). Sharing My Story: Sara. American Diabetes Association. Retrieved from https://diabetes.org/blog/sharing-my-story-sara

St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. (n.d.). Bolusing for High Fat and Protein Meals. Retrieved from https://sthk.merseywestlancs.nhs.uk/leaflets/download/sthk-64c8daf27aff45.66335659

Tandem Diabetes Care. (n.d.). Type 1 Diabetes Food Plans & Food Lists. Retrieved from https://www.tandemdiabetes.com/support/diabetes-education/nutrition/type-1-diabetes-food-plans-food-lists

Temple Health. (n.d.). Practicing Mindful Eating with Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.templehealth.org/about/blog/practicing-mindful-eating-with-diabetes

The Diabetes Center at UCSF. (n.d.). Protein: Metabolism and Effect on Blood Glucose Levels. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9416027/

The Diabetes Council. (n.d.). Bolusing for Fat and Protein. Retrieved from https://childrenwithdiabetes.com/clinical-director/bolusing-for-fat-and-protein/

The University of Alabama. (n.d.). Diabetes 101: Foods & Drinks for Sick Days. Retrieved from https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/diabetes/assets/sickday.pdf

University Health Network. (n.d.). Insulin for Protein and Fat. Retrieved from https://diabeteseducatorscalgary.ca/medications/insulin/insulin-for-protein-and-fat.html

University of California, Davis Health. (n.d.). Type 1 Diabetes Nutrition and Exercise. Retrieved from https://health.ucdavis.edu/children/patient-education/pediatric-diabetes/type-1-nutrition-exercise

University of California, Los Angeles Health. (n.d.). Exercise Guidelines for Type 1 Diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.uclahealth.org/medical-services/endocrinology/diabetes/type-1-diabetes/exercise-guidelines

US National Library of Medicine. (2017). Insulin Dosing for Dietary Fat and Protein in Type 1 Diabetes: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2(2), 1-6. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5686679/